When “Pass” Isn’t Enough: The Hidden Dangers of Pass/Fail Testing in Product Design

In September 2016 I flew to Colorado for some training and didn’t think much of it. But just a couple of weeks later I would’ve been prevented from getting on the plane. Why? Because I had a Galaxy Note 7 in my pocket. These phones were banned from flights after multiple reports of fires, and Samsung had to recall them globally. Even some replacement units caught fire.

In my research I came across this comment from Battery University, an educational site maintained by Cadex Electronics, “The batteries recalled … had passed the UL safety requirements – yet they failed under normal use.” However, that quote wasn’t even about the Note 7! It referred to the 2006 Sony laptop battery recall, when more than four million batteries were pulled from the market because of fire risks. Ten years later, nearly the same story was repeated with the Note 7.

If a design passes formal safety tests, how and why do real-world failures still happen? This raises a deeper question about how we test designs and interpret results.

What Pass/Fail Testing Really Is and Isn’t

A pass/fail test is the simplest kind of verification and represents level 0 on the continuum. You check whether something meets a threshold and record a binary result, pass or fail. It is common in standards such as UL, IEC, and CE where compliance is the goal. That works fine for safety certification, but it removes the nuance of how close something was, why it failed, or what happens when conditions vary.

The advantages are clear: it’s easy to perform, quick to interpret, and cost-effective. But its purpose is verification, not exploration. It tries to take all the critical thinking and simplify everything into a yes or no decision. That simplicity comes with a price.

The limitation is built in. A unit either passes or fails, with no information about variation or proximity to the threshold. It provides no diagnostic value and no opportunity for learning.

In many companies, test results become a management scoreboard. A line of green checkmarks gives a sense of progress, but that is illusion. The real aim of testing should be to expand understanding of how materials, environment, and assembly interact. Pass/fail hides that learning opportunity and promotes a culture of “meeting spec” rather than understanding variation.

Most organizations don’t lack data; they lack structure and context. Even when test data is collected, it’s often scattered across spreadsheets, emails, and lab reports, disconnected from the decisions it’s meant to inform. Without a system that ties test results back to design intent and real-world conditions, the learning potential is lost.

That’s where tools like Twinmo help: by connecting data, decisions, and context so that every test contributes to organizational knowledge—not just compliance.

Questions a Pass/Fail Test Cannot Answer

In the sequential, question-first approach I emphasize, a pass/fail test leaves many questions unresolved. Such as how close the unit was to the threshold, how does the unit perform under different noise conditions, or what design factors influenced the outcome. Even if every sample passes, can we be sure it will remain safe in the field?

Is It a Good Test?

In the first article of this series, I offered criteria for evaluating test approaches across a spectrum of sophistication. Let’s see how pass/fail testing measures up:

Serve a clear purpose: The purpose is simple, but it exists. Verify whether a unit meets a threshold. Notice how this purpose says nothing about discovery or learning.

Inference that supports practical and statistical conclusions: No. It falls short here. Many critical questions remain unanswered because the inference space will be small.

Reflect real-world variation: You could attempt to simulate worst-case conditions, but the result would still be a point estimate. There is no variation represented in this style of testing.

Connect to design or process decisions: Pass/fail tests simplify decisions, which might speed up projects, but it hides uncertainty. The quality of decision-making is unknown until failures happen in the field. That’s a risky way to run development.

Return on investment: Almost no knowledge is gained, so the cost of the test must be very minimal to make any sense.

Overall, this approach only answers, “Does it pass?” and comes nowhere near the better question “How and why does it perform this way?”

To see how easily this limitation hides in day-to-day development, let’s look at a simple example.

Heating Element Example

A small appliance manufacturer is developing a new heating element for one of its countertop products. The design team has spent months refining the balance between heat output, efficiency, and cost, while also keeping a close eye on safety. As part of the validation phase, the test engineers build a setup to simulate the worst-case customer conditions that might cause overheating or even a fire. The goal is to confirm that the design remains safe under the harshest use.

They test 40 prototype units, running each through an extended duty cycle that accelerates wear and exposes weaknesses early. After several days, every unit passes without issue. The data look great, and confidence in the design grows. The test report is completed with a final summary conclusion of “0 failures out of 40 tested.” Based on these results, the team feels confident that the design is sound and moves the project forward.

When the first production run is complete, another 40 samples are pulled for verification. These are built with production tooling and materials, representing the final product that customers will use. Once again, every test passes. Two rounds of testing and zero failures seem to confirm that the heating element is ready for launch. Management approves the design, and production begins.

The process looked disciplined and professional yet hidden in that confidence was a subtle error with potentially costly consequences.

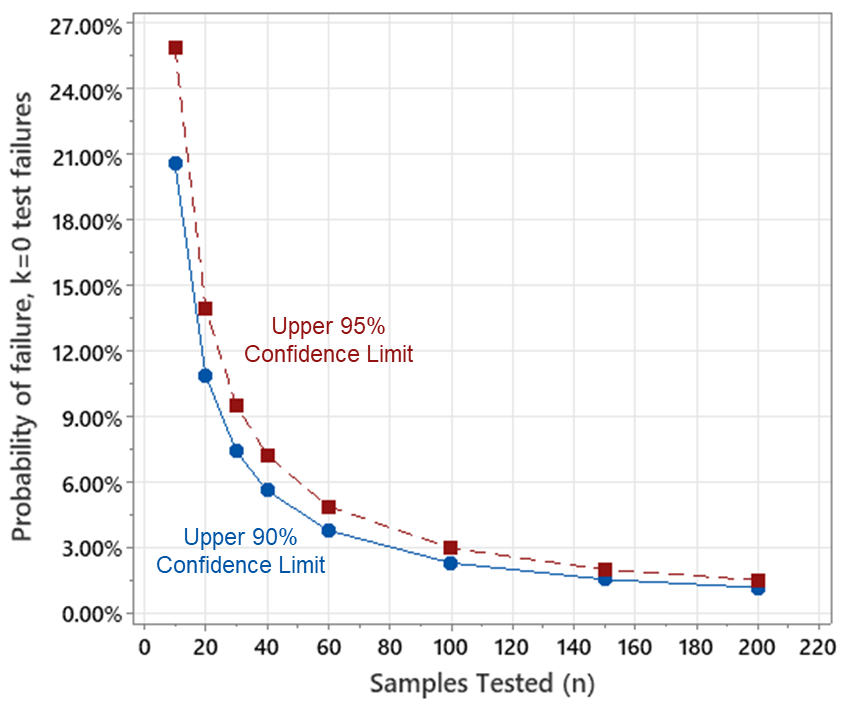

This “zero failures in n tests” mindset is common, and it shows the fundamental limitation of pass/fail testing. “Zero failures” in the lab does not mean “zero risk” in the field. Unless your sample size is comically large, the assurance you get from this kind of testing is weak. The team celebrated the absence of failures without asking what that result truly means. Forty samples with no failures might sound reassuring, but statistically it only tells you that, with 95% confidence, the true failure rate could still be as high as about 7.2%.

To build some understanding and see how misleading it can be, here is how we can quantify the risk even when zero failures are observed like I did above.

If you test n = 40 samples and observe k = 0 failures, the upper bound for the true failure rate (at 95% confidence) can be estimated as:

- The probability of zero failures if the true failure rate is p can be shown as (1 - p)ⁿ

- Solve for p such that (1 - p)ⁿ = α (for α = 0.05, or 95% confidence)

- p = 1 - α^(1/n) = 1 - 0.05^(1/40) ≈ 0.072 (7.2%)

- So with 95% confidence, the true failure rate is less than or equal to 7.2%

In real life, conditions drift, environments vary, and Murphy’s Law applies. Things are often worse than our models predict.

This graph shows how the probability changes with varying levels of sample size, assuming no parts fail in any test. You can see how fast it climbs up when the sample sizes are small. And remember this is assuming no failures in your entire sample.

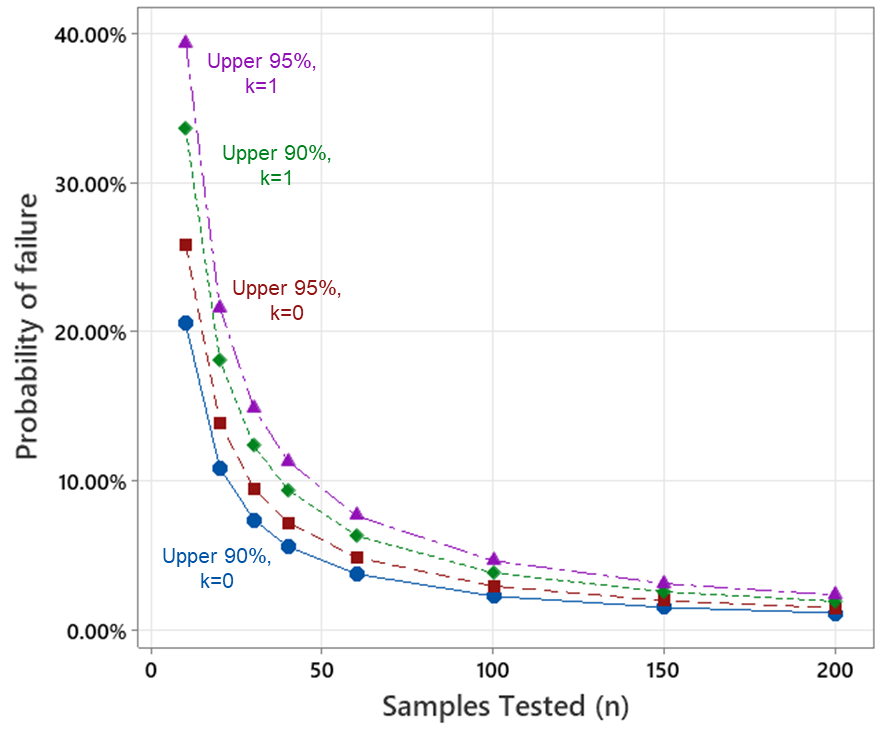

As soon as you get even just 1 failure, things look even worse. It’s possible to calculate any combination of samples and tests to see what it means regarding the possible field risk.

However, as we’ve discussed, this approach are not the best way to proceed. We can gain more knowledge about a product or process more efficiently by using a better testing method.

Beyond Pass/Fail

Pass/fail testing will always be necessary for compliance, but it is not sufficient for learning. The pass/fail model assumes the world is stable and predictable, that every unit either works or doesn’t. But the real world is not binary. Use it when required. Do not rely on it for development. Every test should teach something about variation, margins, and cause and effect. Heat, vibration, and assembly variation all shift the distribution. The goal of good testing is not to declare victory, but to refine the model until it better describes how reality behaves. That is why reliability work relies on time-to-failure data, accelerated life testing, and probabilistic models rather than single snapshots. A product that “passes” today may still fail tomorrow. Not because it violated the spec, but because the test never explored how margins erode with time.

Even Samsung’s batteries passed formal tests before failing catastrophically in real use. The lesson is that passing a test is not the same as understanding a system.

The next step is to treat every test as a source of knowledge. Characterize variation, margins, and boundary conditions. Explore drift and stress. Use the tools of reliability and design of experiments to understand cause and effect.

Even when engineers collect rich data, that learning often stays buried in reports or shared drives. Without a connected system to capture test conditions and context, teams end up relearning the same lessons later. Tools like Twinmo help close that gap by turning testing into a continuous feedback loop—linking results across teams and programs so variation can be understood, not rediscovered.

Testing is not a hurdle to clear, it is feedback to learn from. Pass/fail is not the story. Variation is.