One Factor at a Time: When We Start to Learn, but Not Enough

One Factor at a Time: When We Start to Learn, but Not Enough

In 2021, Ford recalled more than 115,000 Super Duty trucks after reports of steering columns separating under certain conditions. The company had followed its standard launch and validation process. The design passed all torque and durability tests, supplier PPAPs were approved, and the safe launch process ran as planned. Everything looked solid on paper.

Two months after vehicles reached customers, some began showing looseness in the steering column. It wasn’t catastrophic, but it was unsettling. Investigations traced the issue to a subtle variation in the assembly of the upper steering shaft. When tolerances stacked a certain way, the joint could pull apart under load.

From the reports available, testing seems to have focused on nominal builds and expected conditions. The issue appeared only when normal manufacturing variation pushed the parts slightly outside of ideal alignment. The team had tested to confirm the design, not to learn how it behaved when variation showed up.

That’s the gap between testing for compliance and testing for understanding.

The Next Step on the Test Continuum – One Factor at a Time

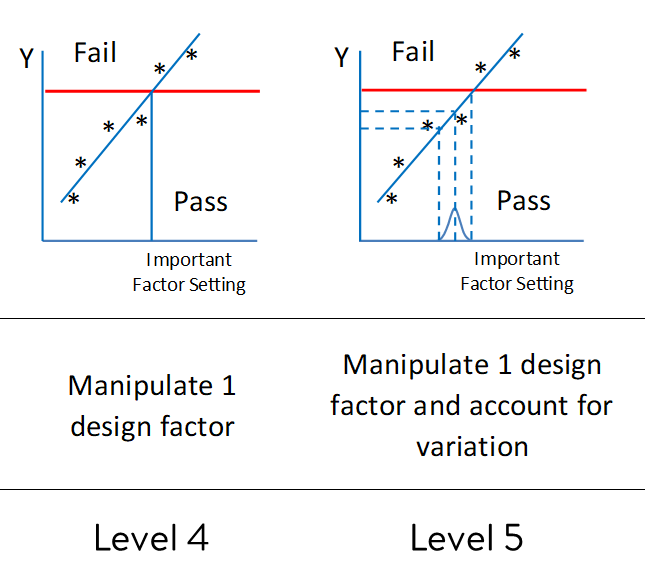

At this stage, the test philosophy is shifting. Instead of simply checking whether a product meets a threshold, engineers start to ask, “What happens if we change something?” One design factor (such as hardness, thickness, or voltage) is adjusted across several settings while all else is held constant. This is the basis of the scientific method many of us learned in school. This article will apply to levels 4 and 5.

This One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) method brings some learning, but it’s still flawed. We can visualize how performance changes with a controllable factor, but by holding everything else constant, we only learn within a narrow slice of the system. More importantly, it prevents critical discovery of interactions. Better experimental methods will be covered in the next two articles.

OFAT is often where test programs stall. It feels scientific because it’s structured and data-driven, yet without accounting for manufacturing or environmental variation, the results can be misleading. We might conclude “stiffness is insensitive to thickness,” when in reality the natural process noise in thickness or material strength might overwhelm that effect in production.

This test type sits midway between simple variable-response testing and a true designed experiment. It allows for limited discovery, but not generalization.

Representing Real-World Variation – Combining OFAT with Process Sampling

An improved OFAT approach is to intentionally manipulate one factor while sampling parts that represent real process variation. This could be different production lots, tool cavities, material suppliers, or shifts. Anything the project team has identified on their process walks, or structured brainstorming activities during development.

Now the test output includes both design-factor effect and process noise, allowing the engineer to study main effects while gauging robustness.

This approach captures the spirit of learning without the full cost or complexity of a DOE. It starts to bridge the gap between controlled lab understanding and messy production reality.

A platform like Twinmo supports this by keeping test context intact—linking which lots, conditions, and factor levels each data point came from. That structure prevents the common trap of flattened spreadsheets that hide the very variation we’re trying to study.

Is It a Good Test?

Let’s evaluate this stage using the same five criteria:

Serve a clear purpose: Yes. The test seeks to understand how a specific design factor affects a response.

Inference that supports practical and statistical conclusions: Somewhat. A clear trend may be observed, but conclusions are limited to the tested factor and nominal conditions.

Reflect real-world variation: Partially. If representative samples are used, some process variation is captured, but environmental factors or combined interactions remain untested.

Connect to design or process decisions: Yes, for that single factor. Teams can identify approximate sensitivities and refine design margins. This, however, can lead to potential misunderstandings since interactions cannot be uncovered.

Return on investment: Useful in niche scenarios, but a multifactor DOE will yield more knowledge for similar effort.

Overall, this method is progress. It teaches cause and effect for one factor while beginning to recognize process noise, but it’s still short of revealing the full system behavior.

Temperature-pressure wafers Example

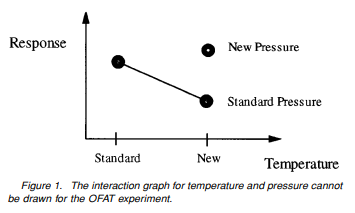

In one published example, an engineer wanted to compare pressure and temperature settings for a gas anneal process. The experiment used 48 wafers divided into three runs: standard pressure and temperature, standard pressure with a new temperature, and new pressure with the new temperature. On paper, it looked like a sound plan. Each run had 16 wafers, and averages could be compared.

But the design had a problem that is not obvious at first glance. It was a one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) test. Because there was no run at new pressure with standard temperature, the engineer could not separate the effects of pressure and temperature or detect any interaction between them. The experiment could show whether the process behaved differently at the new temperature or at the new pressure, but not whether those factors influenced each other.

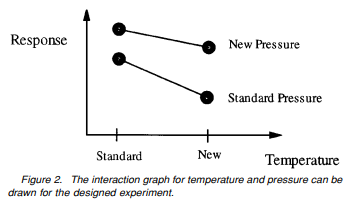

A simple two-factor, two-level design would have solved this. By running four combinations instead of three, standard and new levels of both temperature and pressure, the same 48 wafers could have been used more efficiently. Each factor’s effect would have been estimated using all the data, and the interaction between pressure and temperature could be measured directly. The difference in precision is quantifiable. The variance of each effect estimate in the OFAT plan was about 50 percent higher than in the factorial design.

This example shows how OFAT thinking and narrow sampling can limit what can be learned, even when averages look solid. Designed experiments and rational subgrouping use the same resources to provide clearer inference about how variables interact. The lesson applies broadly in testing. More complete sampling of factor combinations turns disconnected results into knowledge that supports learning and improvement.

Reference: Czitrom, V. (1999). One-Factor-at-a-Time Versus Designed Experiments, The American Statistician.

Beyond the Nominal

Following procedures and meeting PPAP are necessary step, but not sufficient ones.

Real knowledge comes from exposing a design to both intentional changes and unintentional variation. When engineers begin to blend factor manipulation with representative sampling, they move from “Does it pass?” toward “How does it behave?”

That question “How does it behave?” is the doorway to experimental design and robustness engineering, which we’ll explore in the next article.

And with connected tools like Twinmo, that learning doesn’t end when the test report is written. It becomes part of the organization’s shared understanding, ready to inform every next design and validation.