How Test Engineering Evolves: From Checking to Learning

Did you know that in 2025 Candy had to perform a costly dryer recall due to a risk of fires? Even more concerning, the initial recall happened in May and repairs were deployed, but by August the company announced that even the repaired units could still catch fire. Customers were told to unplug their dryers and stop using them altogether.

Failures like this happen more often than people realize, even for products that have been around for years. So why does this keep happening? Do manufacturers not test their products? Many customers might think that, but of course they do. The issue is that many tests are designed to pass a standard rather than to teach us something. Even when valuable insights do emerge, they’re rarely captured in a consistent system where they can inform future designs or decisions. The organization ends up learning the same lessons again and again. That’s where tools like Twinmo can help. By connecting data from tests, field performance, and design revisions, Twinmo helps organizations build a living memory of what’s been tried, what worked, and why. Instead of rediscovering the same problems, engineers can spend more time engineering and test technicians can spend more time testing.

That raises an important question: why do we put so much confidence in a test simply because it’s called a test?

Test engineering is the work of properly designing, executing, and analyzing tests so that we actually learn something. Not all tests are created equal, and many do not tell us what we think they do. Too often, organizations test to check rather than to learn.

The simplest type of test is a basic pass/fail assessment. No variable data is collected. The product is verified against a criterion, and the result is recorded as either pass or fail.

A step up from that is collecting variable data instead of simple pass/fail results. This allows us to record actual values and build a distribution across multiple samples. Now we begin to recognize that not all parts are the same and that manufacturing variation exists. The level of sophistication can range from random sampling to intentional selection from the low and high tolerance limits, or a rational, event-based subgrouping plan.

If we want to move beyond checking and start predicting though, our testing must include the manipulation of design factors in combination with variation in the product, process, and environment. This variation in inputs or conditions is what we call noise.

To generate learning, the goal of testing should be to understand how a design or process responds under different noise conditions. A robust design meets customer expectations even when those conditions vary. Without observing failures or weaknesses, engineering teams cannot make meaningful improvements. That’s why Test Engineering should play a central role in both process and product development.

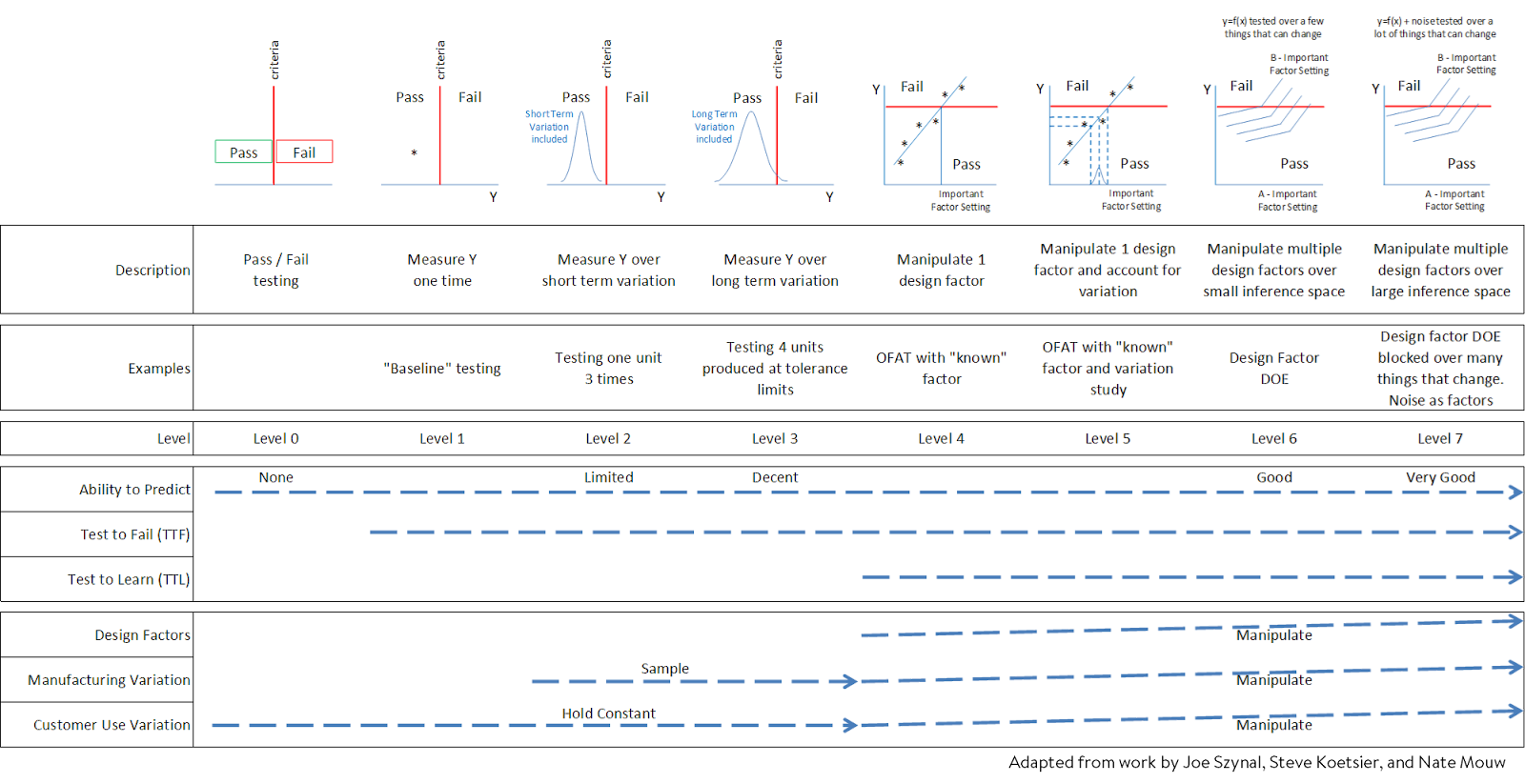

Understanding how tests evolve in complexity helps clarify what kind of learning each one can provide. We will propose categorize these from level 0 to level 7 per the chart above. This spectrum of testing sophistication provides a useful framework for understanding how testing can evolve from simple verification to real learning. Over the next several articles, I’ll use this framework to explore different approaches to testing, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each.

Before comparing these methods, it helps to agree on what makes a test good.

A good test should:

- Serve a clear purpose

- Allow for inference that answers project questions or supports practical and statistical conclusions

- Include variation that reflects the real customer environment for both use and perceivable misuse

- Connect directly to design or process decisions

- Provide a reasonable return on investment, where the cost of the test is proportional to the value of the knowledge gained.

If your testing is not teaching you something new, it may be time to rethink your approach. The question should not be “Does it pass?” but rather “How and why does it perform this way?”

The Vibration Mount Example

An automotive supplier is developing a new vibration isolation mount for an upcoming vehicle platform. The current mount, “Design A,” has been in production for several years with only minor field complaints. A redesign, “Design B,” promises lower cost and weight savings through a new polymer blend and revised geometry.

The design team expects at least a 10 percent cost reduction while maintaining the same durability and NVH (noise, vibration, and harshness) performance. Early finite element models suggest similar stiffness and natural frequencies. To move quickly, the team decides to validate Design B through the same test specification historically used for mount approval. It was originally intended for supplier quality control, not for validating design changes, but it was applied here for convenience. Afterall they’ve used this test for years, and it passed the most recent MSA (Measurement System Analysis). Surely, that means it’s perfect for this project.

That test involves cycling a sample of mounts under a defined load for a fixed number of repetitions, for example 100,000 cycles, and confirming that no visible cracking or separation occurs. There is an upper limit of no more than 6% of parts in the sample that show defects. The logic is simple: if a mount passes this test, it is considered durable enough for service.

Design A has always passed. To everyone’s relief, Design B also passes. The lab reports the test result as no statistically significant difference. Management and the project team deem the design ready, note the successful cost savings on their department scorecard and the new design is released to production.

Within months of vehicle launch, warranty claims rise for cabin vibration and early mount failures. Now upper management wants answers. The savings are quickly eroded as emergency measures are implemented, and the firefighting begins to recover.

Unfortunately, the entire premise was flawed. A pass/fail durability test cannot tell whether performance has degraded; it only tells you if something survives the test conditions. Applying sound Test Engineering principles would have led to a different validation strategy. I will cover what should have been later in this series.

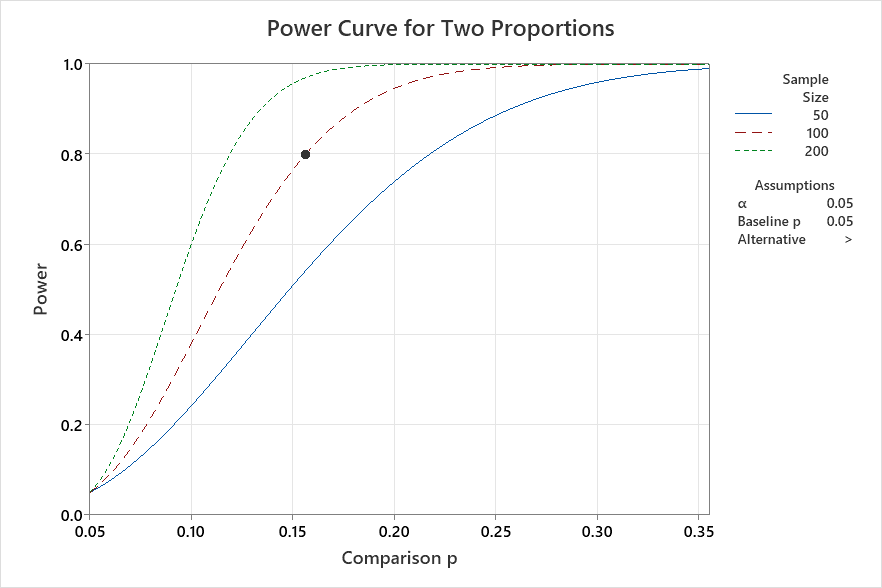

For now, consider the math behind the result. The engineers used a standard two-proportion test to compare failure rates between designs. This is an enumerative approach. Let’s examine an illustrative example two-proportion power and sample size analysis to show why the “Fail to Reject” conclusion shouldn’t be surprising.

The chart above compares sample sizes of 50, 100, and 200. I’m being generous because that sounds large, but for binomial data, it’s actually quite small. Assuming a one-tailed test, 80 percent power, and a current failure rate of 5 percent, we would only detect a difference if Design B’s failure rate climbed above 15 percent. Even with 200 samples (which is probably more than they’d test), we could detect a smaller difference, but the degradation would still need to be more than double. That is a big drop in performance to go unnoticed.

So yes, if organizations are using tests like these, it’s not surprising that degradations slip through. Over time, small cost-saving changes are justified through similar testing, performance slowly degrades, and competitors start taking market share. This is essentially asking your customers to be your validation lab, and that’s no way to run a business.

The data says everything is fine until customers say otherwise.

That’s the real issue at the heart of this series. Most organizations are doing plenty of testing, but much of it is checking rather than learning. In the coming articles, we’ll explore how test design can evolve from simple pass/fail assessments to experiments that include design factors, process variation, and environmental noise. Each will include a practical example and analysis.

Moving from checking to learning isn’t just about better test design; it’s also about better knowledge flow. When data and context from each test are captured and shared through a connected system like Twinmo, patterns start to emerge that individual teams might never see. That’s when testing stops being an isolated activity and starts becoming an organizational advantage.

If you’re responsible for testing, design validation, or field performance, this series will help you see what level of test engineering you’re practicing today and how to take it further. I’ll explore how tests can evolve from simple verification to learning in the next article. If you’re interested in how tools like Twinmo can support that journey, visit twinmo.ai