Expanding the Inference Space – Considering Noise as well as the Design

On July 14, 1999, during construction of Milwaukee’s Miller Park, a massive crane nicknamed Big Blue was lifting a 450-ton roof section. The previous nine lifts had gone smoothly, and the specialized crane had been designed and tested for the heavy task (Milwaukee Magazine).

But that day, wind gusts were reported above the safe limit and the soft soil beneath the tracks began to settle unevenly (Medium, CBS News). The roof panel caught the wind like a sail, creating unexpected side loads. Within seconds, the boom buckled and the crane collapsed, killing three ironworkers and halting construction.

The crane’s design had been verified, but only under certain conditions. The real-world combination of wind, soil movement, and shifting load pushed it beyond those limits. Calculations that predict failure points can guide construction safety, but without representative data, those predictions can miss the mark. Safety procedures should have prevented the lift given the environmental noise, but the cultural factors behind the decision are the subject of another article.

What are you working on right now that could benefit from some noisy experiments? Have you tested how your solution holds up under variation, not just ideal conditions? By expanding the inference space intentionally, experimenters can see how designs behave under real-world noise.

On top of this, make your workflow efficient. Twinmo helps teams connect design of experiments with automated testing and real-time analytics, making it easier to study how designs perform under variation.

Definition of terms

Some of these have been mentioned in prior articles, but since they are central to this one, it’s worth defining them clearly:

Inference Space – The range of conditions over which your data and conclusions can be trusted. Outside this space, predictions are uncertain and additional testing is needed.

Design of Experiment (DOE) – A structured method for testing multiple factors at once to see how they influence an outcome. DOE helps you understand the system, not just whether a single factor “works” or “fails.”

Design Factors – The variables you actively change in an experiment to find optimal settings. Once determined, these factors are controlled in the final product or process.

Noise Factors – Variables that can be known or unknown and naturally vary in the environment, usage, or materials and are not controlled during operation. Including them in testing shows how a design performs under real-world conditions.

Interaction – When the effect of one factor depends on the level of another. Interactions often go unnoticed in single-factor tests but can be critical to understanding the system.

Robustness – The ability of a product or process to perform consistently despite variation in noise factors. A robust design handles real-world conditions without failure.

The Final Step on the Test Continuum – DOE with Noise Factors

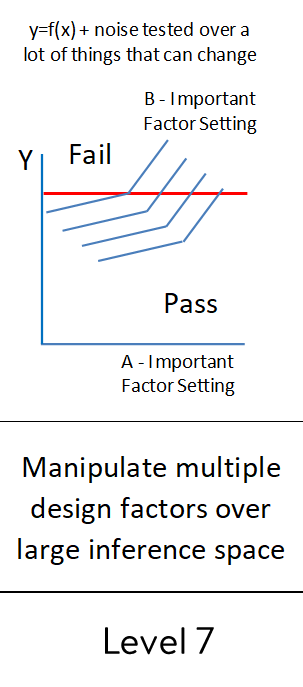

Design of Experiments, or DOE, is more than a method for testing multiple factors at once. When noise factors are included, it becomes a tool for understanding how a system performs under real-world variation. This is what brings us to level 7 test engineering. Instead of changing one variable at a time, DOE varies both design factors and sources of variation in a planned, structured way. This approach reveals not only the effect of each factor but also how factors interact with one another and how robust the system is to environmental or operational changes.

In practice, DOE with noise factors lets teams explore the design and inference space efficiently. Instead of running dozens of separate tests, a well-designed experiment can show which factor combinations consistently meet performance goals under realistic conditions. It transforms testing from trial-and-error into a learning process that uncovers both sensitivities and interactions that matter in the field.

This approach provides a clear map of the system’s behavior, not just isolated snapshots from one-factor-at-a-time tests. By including noise factors, teams can see where designs are strong, where they are fragile, and where trade-offs exist. The results support better decision making, allowing development of response surfaces and robustness strategies that improve reliability, performance, and confidence in real-world operation.

Is It a Good Test?

Let’s evaluate this stage using the same five criteria:

Serve a clear purpose: Yes, specifically expand inference space and evaluate robustness. The test seeks to understand not only how design factors affect the response, but also how the system behaves under realistic variation.

Allow for inference that supports practical and statistical conclusions: Definitely. Including noise factors lets teams assess the significance of the design over varying noise conditions.

Include variation that reflects the real customer environment: Significantly. This step on the test continuum is the only one that truly meets this criteria.

Connect directly to design or process decisions: Absolutely. The type of data generated by these experiments allow for fundamental physics based response curves that enable decisions for not only this project but similar ones in the future.

Provide a reasonable return on investment: High. A well-planned DOE with noise factors uncovers more knowledge in the same or slightly more effort than a single-factor test, because it highlights both main effects and interactions that matter in real-world conditions.

Overall, a sequential DOE approach which concludes with this type of testing brings true discovery and a deeper understanding of the system. It reveals which factors are robust, which are sensitive, and how the system performs under real-world variation, turning test results into actionable design insight.

Example – Learning from Noise in a Semiconductor Process

To make this idea of expanding the inference space more concrete, consider an example from Montgomery’s Design and Analysis of Experiments (Example 12.2).

An engineering team in a semiconductor manufacturing facility was studying a process with two controllable variables, temperature and gas flow rate, and three noise variables representing sources of variation that could not be easily controlled in production.

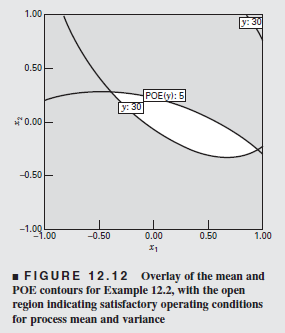

Instead of holding those noise variables constant or ignoring them, the team deliberately included them in the design. They used a combined array structure, a modified central composite design (CCD), that allowed them to model a second-order relationship for the controllable variables while also estimating main effects of the noise variables and the interactions between control and noise factors. This type of design allowed them to generate a prediction model for what the design factors were doing including their effects in various levels of noise.

Using that information it’s possible to plot how the design factor settings will respond at various levels given that some setting combinations are more robust than others. This response surface plot shows the region acceptable for the desired mean response as well as the actable process standard deviation. An output like this would not be possible without including the noise factors in the DOE.

The fitted model showed that one of the noise variables had a significant main effect on the response and interacted with the control factors. That meant the process was not just being disturbed by random variation, it was sensitive to it. Certain combinations of temperature and flow rate amplified the impact of that noise, while others reduced it.

By exploring those interactions, the team did more than find an optimal setting. They found a region of operation where performance was stable even when the noise shifted. That is the essence of robust design, widening the inference space to understand how the system behaves under the conditions it will actually face.

When engineers include noise variables in their design, they are not making the experiment more complicated. They are making it more useful. They are learning how to make the system less fragile.

Beyond the Nominal

Including noise factors in your experiments transforms the way we learn about a system. A simple one-factor-at-a-time test can teach you about cause and effect in ideal conditions, but it rarely reveals how your design behaves under real-world variation. By using a DOE with noise factors or a combined array, teams expand their inference space and uncover both main effects and interactions that truly matter.

The semiconductor example shows this clearly. By modeling not just the mean response but also the variance across noise conditions, the team could identify regions of the design space that were both high-performing and stable. This is the essence of robust design: understanding not just what works, but what works reliably.

For engineers and product developers, the lesson is simple. Designing experiments that include noise isn’t just more realistic, it’s more useful. It turns data into insight, and insight into designs that perform consistently for the people who actually use them. Platforms like Twinmo make it easier to implement these DOE strategies efficiently, helping teams build knowledge over time without unnecessary extra processing.