Designing for Success — One Factor at a Time Isn’t Enough

In recent years, thermal failures in cordless power tools have surfaced in both research and safety investigations. A 2012 study, Thermal Distribution of Temperature Rise for 18 V Cordless Impact Drill, documented gearbox temperatures exceeding 130 °C and motor temperatures around 116 °C under heavy load conditions (Syed Ahmad Alhabshi, 2012). More recently, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has issued multiple warnings and recalls for cordless drills due to overheating, melting, or fire hazards, with problems reported not only from motors but also from switches and internal wiring (CPSC).

How can this happen? Often, organizations work in department silos and investigate by examining one factor at a time in a sequence. Separate teams might optimize the airflow path first, move on to the winding design, then to switch or wiring insulation, testing each one in isolation. This approach feels methodical, even scientific, because it’s what many of us were taught: isolate one variable, measure its effect, then move to the next.

But that mindset breaks down in complex systems. Airflow affects motor temperature, which changes the current drawn through switches and connectors, which in turn affects local heating. In the real world, everything happens at once, and the interactions among design factors determine performance and safety far more than any one factor alone.

Utilizing a platform like Twinmo enables team collaboration to break down department silos, as well as visualizing and organizing learning between experiments to track the system-level picture. This is especially important in today’s fast paced global development market where teams could be anywhere while contributing to the same project.

The Next Step on the Test Continuum – Design of Experiments

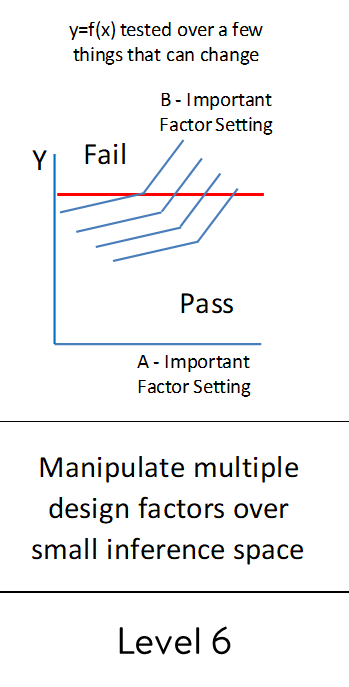

Design of Experiments, or DOE, is a structured method for testing multiple factors at the same time to see how they influence a result. Instead of changing one variable and keeping everything else constant, DOE varies several variables together in a planned way. This allows experimenters to identify not only the effect of each individual factor but also how factors interact with one another. Using a planned experiment with multiple factors brings us to level 6 testing. Levels 1-5 have represented methods with various compromises, level 6 represents the true starting point for most test engineering.

In practical terms, DOE lets teams explore the design space efficiently. Rather than running dozens or hundreds of separate tests, a well-planned DOE can reveal patterns and relationships with a fraction of the effort. It turns testing from a trial-and-error process into a learning process, providing insights about which combinations of factors produce the best outcomes.

It provides a clear map of the design space instead of isolated snapshots from one-factor-at-a-time experiments. It also keeps system-level performance at the forefront, ensuring that the right design decisions can be made. With system-level knowledge, trade-off curves and response surfaces can be developed to improve decision making in product development or process improvement.

The case for DOE

Without DOE, many teams rely on simpler approaches such as trial-and-error or one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) testing. Trial-and-error changes parts or settings almost randomly and observes the outcome. It can occasionally work for simple problems but is slow, inefficient, and provides little to no understanding of why changes succeed or fail.

OFAT feels more systematic because a single variable is adjusted, optimized, and then the next variable is tested. Its limitation is that interactions between factors are missed. Changes that appear beneficial in isolation may cause problems when combined with other factors, leaving critical insights hidden.

Design of Experiments overcomes these limitations by varying multiple factors together in a balanced (equal observations at each level) and orthogonal (factor effects and interactions can be independently estimated) way. DOE is efficient, requiring fewer tests than trial-and-error while providing deeper understanding. It reveals interactions, highlights which factors matter most, and keeps system-level performance in focus.

A simple factorial table can illustrate this. By systematically testing all combinations of selected factors at two defined levels (commonly referred to as a minus level and a plus level), DOE makes both main effects and interactions visible, providing a map of the design space that trial-and-error or OFAT cannot produce. You can see how in this example speed, octane, and tire pressure are all varied to two levels to see the effect on mileage.

Is It a Good Test?

Let’s evaluate this stage using the same five criteria:

Serve a clear purpose: Yes. The test seeks to understand how design factors affect a response. And much more so if the experimenter performs the proper up-front planning.

Allow for inference that supports practical and statistical conclusions: Yes. The test reveals not only the main effects of each factor but also interactions between factors. Practical and statistical significance can be assessed within the range of factors tested.

Include variation that reflects the real customer environment: Partially. Design-factor DOE focuses on controllable variables, so environmental or operational noise is not fully represented.

Connect directly to design or process decisions: Yes. Teams can identify which design factors have the greatest impact and make informed adjustments to improve performance.

Provide a reasonable return on investment: Yes. The structured approach allows multiple factors and interactions to be studied efficiently, producing far more insight than OFAT or trial-and-error for a similar number of tests.

This test is effective for exploring design factors. It uncovers important interactions and guides design decisions, but the next step is to include noise factors to see how the design performs under real-world variation.

Example – An Experiment with Deep Groove Bearings

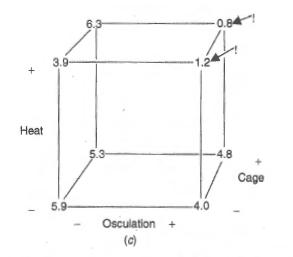

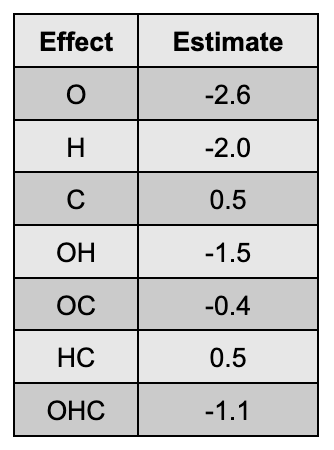

An example from Box, Hunter, and Hunter (2005), Statistics for Experimenters, illustrates the benefits of DOE. Hellstrand (1989) conducted an experiment with the objective of reducing the wear rate of deep groove bearings. In the experiment, three factors each with two levels were studied: osculation (O), heat treatment (H), and cage design (C).

After completing the runs and studying the data, two out of the eight runs showed drastically different results from all the rest. High osculation and high temperature together produced a critical mix, yielding bearings that had an average failure rate one-fifth of that for standard bearings. This effect was confirmed through follow-up experiments. Hellstrand reported that this large and unexpected interaction had profound consequences.

The effects were calculated by taking the average at the plus level minus the average at the minus level for each factor and interaction. These can then be assessed for both practical and statistical significance. An interaction plot clearly shows the discovery: the combination of osculation and heat treatment produced a dramatic improvement in bearing life.

Learning Through Designed Experiments

When teams reach this stage of testing, they’ve moved from observing symptoms to learning how their system truly behaves. A well-run DOE exposes relationships that single-variable testing can’t reveal, turning cause and effect into something visible and measurable. The bearing example shows how an interaction can dominate the story, an effect no amount of trial and error would likely uncover.

Since many experimenters still have little knowledge of multifactor design, there are countless interactions waiting to be discovered. DOE makes experimentation deliberate learning. And when teams pair that mindset with structured collaboration tools like Twinmo, they can capture what was tested, why it mattered, and how design choices interact, turning experiments into shared organizational learning instead of isolated events.

As the next step will show, introducing noise factors brings that learning closer to the messy, variable reality our products live in and allows teams to expand inference space and design products and processes that are robust to the chaos of real life.